Thursday, May 31, 2007

Wednesday, May 23, 2007

Meeting Everyone

Last night was the read-through and the script really came to life in a way I had not imagined based on my readings of the play. After perusing many reviews and seeing production stills online from other cities' premieres of the play, I was wondering how this production would differ and how unique the casting might be.

Shawn spoke at the beginning about the play being about "making belief" which is essentially "make-believe" and his reasons for wanting to produce the play. It touched on my reason for wanting to dramaturg it - because it cleverly addresses dramatic and harsh realities that I feel warrant addressing in our society, and how better to do so than through theatre.

Our cast is quite an impressive collection of talent incorporating a whole range of backgrounds, from those newer to the Boston theatre scene to more veteran thespians of Beantown. I sensed that everyone was really happy to be there and excited as the reading progressed, showing more and more depth to the play in the exchanges, all at once ridiculously funny and heart-breaking.

Here is the line-up of actors and a few things about their affiliations or past productions that I could find online. I think it's a testament to the collaborative spirit of Boston theatre that so many prominent and passionate theatre artists can come together like this. Speaking with a few of them after the reading, I anticipate a rich and fulfilling experience had by all!

Daniel Berger-Jones

http://www.actorsshakespeareproject.org/season3/titus.html

Amanda Hennessey

www.essayons.org (under Creative)

Rachael Hunt

John Kuntz

http://www.bu.edu/bpt/grad/kuntz.html

http://www.11centralave.org/Documents/John.html

http://www.actorsshakespeareproject.org/company/index.html

http://www.boston.com/ae/music/articles/2004/10/03/another_local_artist_sees_calderwood_debut

Greg Maraio

www.wayplays.com (under Who's Who)

Mark VanDerzee

www.companyone.org (under Board of Directors)

Shawn spoke at the beginning about the play being about "making belief" which is essentially "make-believe" and his reasons for wanting to produce the play. It touched on my reason for wanting to dramaturg it - because it cleverly addresses dramatic and harsh realities that I feel warrant addressing in our society, and how better to do so than through theatre.

Our cast is quite an impressive collection of talent incorporating a whole range of backgrounds, from those newer to the Boston theatre scene to more veteran thespians of Beantown. I sensed that everyone was really happy to be there and excited as the reading progressed, showing more and more depth to the play in the exchanges, all at once ridiculously funny and heart-breaking.

Here is the line-up of actors and a few things about their affiliations or past productions that I could find online. I think it's a testament to the collaborative spirit of Boston theatre that so many prominent and passionate theatre artists can come together like this. Speaking with a few of them after the reading, I anticipate a rich and fulfilling experience had by all!

Daniel Berger-Jones

http://www.actorsshakespeareproject.org/season3/titus.html

Amanda Hennessey

www.essayons.org (under Creative)

Rachael Hunt

John Kuntz

http://www.bu.edu/bpt/grad/kuntz.html

http://www.11centralave.org/Documents/John.html

http://www.actorsshakespeareproject.org/company/index.html

http://www.boston.com/ae/music/articles/2004/10/03/another_local_artist_sees_calderwood_debut

Greg Maraio

www.wayplays.com (under Who's Who)

Mark VanDerzee

www.companyone.org (under Board of Directors)

Tuesday, May 22, 2007

First Production Meeting

The 1st production meeting last night covered mainly scheduling and target dates for set, lighting, and sound design. An interesting concept arose that Shawn has in mind - to possibly incorporate a band that doubles as the cactus and sunflower, specifically the idea of working with Human Wine. Their myspace at http://www.myspace.com/HUMANWINE has tracks that can be played, as well as read some excerpts from reviews.

If they're not available, I mentioned the possibility of Michael O'Halloran's wife who I saw perform with her band a few years ago and thought their style might be along the same lines, with a more burlesque feel that could work given the adult themes of the play.

Miss Mary Mac! That's her stage name. I just found it online.

A Globe mention at:

http://www.boston.com/ae/theater_arts/articles/2004/03/04/let_them_entertain_you/

That's an old article but I saw a post that she performed in November in Gloucester. So it's a possibility.

UPDATE: a little more digging unearthed her band's site at http://www.sukeytawdry.com

and her email at http://www.sukeytawdry.com/calendar.html which is:

missmarymac50@hotmail.com

If they're not available, I mentioned the possibility of Michael O'Halloran's wife who I saw perform with her band a few years ago and thought their style might be along the same lines, with a more burlesque feel that could work given the adult themes of the play.

Miss Mary Mac! That's her stage name. I just found it online.

A Globe mention at:

http://www.boston.com/ae/theater_arts/articles/2004/03/04/let_them_entertain_you/

That's an old article but I saw a post that she performed in November in Gloucester. So it's a possibility.

UPDATE: a little more digging unearthed her band's site at http://www.sukeytawdry.com

and her email at http://www.sukeytawdry.com/calendar.html which is:

missmarymac50@hotmail.com

Sunday, May 20, 2007

Image Photo 1

From time to time I may run across images that seem to evoke the world of the play, or some essence of it, and I'll post them. A precarious and isolationist tone to this one struck me. The text at its website says: "Dark matter - we can't see it, we can't detect it in any way, and yet it needs to be there in order for the universe to behave the way it does." I found the quote apropos, given our tale of a seemingly dark and unseen friendship.

Workaholism: The 'Respectable' Addiction

By Sid Kirchheimer WebMD Feature (http://men.webmd.com/guide/workaholism)

Reviewed by Louise Chang, MD

In Japan, it's called karoshi -- "death by overwork" -- and it's estimated to cause 1,000 deaths per year, nearly 5% of that country's stroke and heart attack deaths in employees under age 60.

In the Netherlands, it's resulted in a new condition known as "leisure illness," estimated to affect 3% of its entire population, according to one study. Workers actually get physically sick on weekends and vacations as they stop working and try, in vain, to relax.

And here in the U.S., workaholism remains what it's always been: the so-called "respectable addiction" that's dangerous as any other and could affect millions of Americans -- whether or not they hold jobs.

"Yes, workaholism is an addiction, an obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it's not the same as working hard or putting in long hours," says Bryan Robinson, PhD, one of the nation's leading researchers on the disorder and author of Chained to the Desk and other books on workaholism.

The Difference Between Hard Work and Workaholism

"Hard work put us on the moon and discovered vaccinations and built this country," he tells WebMD. "But hard workers generally have some balance in their lives. They sit at their desks and think about skiing. The workaholic is on the ski slopes thinking about work."

Their obsession with work is all-occupying, which prevents workaholics from maintaining healthy relationships, outside interests, or even take measures to protect their health.

"These are people who may have children, but miss Little League games and school plays when they don't have to, not because they have to be at work but because they feel they need to," says Tuck T. Saul, PhD, a psychotherapist in Columbus, Ohio, who frequently counsels workaholics. "They neglect their health to the point of devastating results and ignore their friends and family. They avoid going on vacation so they don't have to miss work. And even if they do go on vacation, they aren't fully present because their mind is still on work.

"As with any other 'aholism,' there is often a lack of understanding as to how their work addiction affects themselves and others," Tuck tells WebMD. "Often, they only realize their problem when something catastrophic happens to them -- their health completely fails or their marriage or relationships are destroyed."

Addicted to Adrenaline

Such was the case with Cheri, a 52-year-old nurse in California. Several years ago, she realized she was a workaholic and has since attended Workaholics Anonymous (WA) meetings once a week -- which like Alcoholics Anonymous -- has its own 12-step recovery program. Now, she volunteers to help others in the group's Menlo Park headquarters.

"I was wildly successful in my career, a very effective worker and my employers loved me," she tells WebMD. "But outside of work ... well, there was no outside of work. I never thought I had a problem until I tried to get into a close relationship, for something like the fifth time. That was my wake-up call, and it probably helped that my partner was in his own 12-step recovery for another addiction at the time. I took the 20-question quiz at the WA web site and 16 [of them] described me to a T. He was getting better and I realized I had my own addiction -- to adrenaline."

Don't laugh. Workaholics can have a physiologic need for that adrenaline rush, says Robinson, a psychotherapist in Asheville, N.C., and professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

"One thing that we do know is that workaholics tend to seek out jobs that allow them to exercise their addiction," he says. "The workplace itself does not create the addiction any more than the supermarket creates food addiction, but it does enable it. Workaholics tend to seek high-stress jobs to keep the adrenaline rush going."

This is true even if they don't work outside the home.

"We're seeing more women workaholics now because women are more visible in the workplace. But it's my belief that even before this trend, workaholics were doing this in the home," says Robinson. "It could be in their parenting to the point where there is nothing else to balance their lives, no hobbies or fun or spirituality, because they spend all their time as the PTA president, running the youth sports league, and being a Scout leader."

Disorders Often Stem From Childhood

Research shows that the seeds of workaholism are often planted in childhood, resulting in low self-esteem that carries into adulthood.

"Many workaholics are the children of alcoholics or come from some other type of dysfunctional family, and work addiction is an attempt to control a situation that is not controllable," he tells WebMD. "Or they tend to be products of what I call 'looking good families' whose parents tend to be perfectionists and expect unreasonable success from their kids. These children grow up thinking that nothing is ever good enough. Some just throw in the towel, but others say, 'I'm going to show I'm the best in everything so [my] parents approve of me.'"

The problem is, perfection is unattainable, whether you're a kid or a successful professional.

"Anyone who carries a mandate for perfection is susceptible to workaholism because it creates a situation where the person never gets to cross the finish line, because it keeps moving farther out," says Saul.

That is why despite logging in mega hours and sacrificing their health and loved ones for their jobs, workaholics are frequently ineffective employees.

Workaholic Styles

"Overall, workaholics tend to be less effective than other workers because it's difficult for them to be team players, they have trouble delegating or entrusting co-workers, or they take on so much that they aren't as organized as others," says Robinson.

In fact, his research indicates four distinct workaholic "working styles":

The bulimic workaholic feels the job must be done perfectly or not at all. Bulimic workaholics often can't get started on projects, and then scramble to complete it by deadline, often frantically working to the point of exhaustion -- with sloppy results.

The relentless workaholic is the adrenaline junkie who often takes on more work than can possibly be done. In an attempt to juggle too many balls, they often work too fast or are too busy for careful, thorough results.

The attention-deficit workaholic often starts with fury, but fails to finish projects -- often because they lose interest for another project. They often savor the "brainstorming" aspects but get easily bored with the necessary details or follow-through.

The savoring workaholic is slow, methodical, and overly scrupulous. They often have trouble letting go of projects and don't work well with others. These are often consummate perfectionists, frequently missing deadlines because "it's not perfect."

Getting Help

What can be done? Counseling is often recommended for workaholics, and support groups, such as Workaholics Anonymous, are beneficial, say the experts.

"It really comes down to recognizing a need for balance in your life," says Robinson. "Working hard is great, but you need to be able to turn if off and savor the other parts of your life -- friends, family, hobbies, and fun."

But many companies often confuse workaholics for hard workers, in essence enabling them on their path to self-destruction.

"I wouldn't say that corporations cause workaholism, but I think they truly support it," says Diane Fassel, PhD, president of Newsmeasures, Inc., a Boulder, Colo., business consulting firm, and the author of Working Ourselves to Death.

"Even though workaholism is the addiction de jour in American corporations, I'm not sure that many companies offer employee-assistance programs for it, as they do for alcohol or drug abuse," she tells WebMD. "Instead they often reward it."

Reviewed by Louise Chang, MD

In Japan, it's called karoshi -- "death by overwork" -- and it's estimated to cause 1,000 deaths per year, nearly 5% of that country's stroke and heart attack deaths in employees under age 60.

In the Netherlands, it's resulted in a new condition known as "leisure illness," estimated to affect 3% of its entire population, according to one study. Workers actually get physically sick on weekends and vacations as they stop working and try, in vain, to relax.

And here in the U.S., workaholism remains what it's always been: the so-called "respectable addiction" that's dangerous as any other and could affect millions of Americans -- whether or not they hold jobs.

"Yes, workaholism is an addiction, an obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it's not the same as working hard or putting in long hours," says Bryan Robinson, PhD, one of the nation's leading researchers on the disorder and author of Chained to the Desk and other books on workaholism.

The Difference Between Hard Work and Workaholism

"Hard work put us on the moon and discovered vaccinations and built this country," he tells WebMD. "But hard workers generally have some balance in their lives. They sit at their desks and think about skiing. The workaholic is on the ski slopes thinking about work."

Their obsession with work is all-occupying, which prevents workaholics from maintaining healthy relationships, outside interests, or even take measures to protect their health.

"These are people who may have children, but miss Little League games and school plays when they don't have to, not because they have to be at work but because they feel they need to," says Tuck T. Saul, PhD, a psychotherapist in Columbus, Ohio, who frequently counsels workaholics. "They neglect their health to the point of devastating results and ignore their friends and family. They avoid going on vacation so they don't have to miss work. And even if they do go on vacation, they aren't fully present because their mind is still on work.

"As with any other 'aholism,' there is often a lack of understanding as to how their work addiction affects themselves and others," Tuck tells WebMD. "Often, they only realize their problem when something catastrophic happens to them -- their health completely fails or their marriage or relationships are destroyed."

Addicted to Adrenaline

Such was the case with Cheri, a 52-year-old nurse in California. Several years ago, she realized she was a workaholic and has since attended Workaholics Anonymous (WA) meetings once a week -- which like Alcoholics Anonymous -- has its own 12-step recovery program. Now, she volunteers to help others in the group's Menlo Park headquarters.

"I was wildly successful in my career, a very effective worker and my employers loved me," she tells WebMD. "But outside of work ... well, there was no outside of work. I never thought I had a problem until I tried to get into a close relationship, for something like the fifth time. That was my wake-up call, and it probably helped that my partner was in his own 12-step recovery for another addiction at the time. I took the 20-question quiz at the WA web site and 16 [of them] described me to a T. He was getting better and I realized I had my own addiction -- to adrenaline."

Don't laugh. Workaholics can have a physiologic need for that adrenaline rush, says Robinson, a psychotherapist in Asheville, N.C., and professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

"One thing that we do know is that workaholics tend to seek out jobs that allow them to exercise their addiction," he says. "The workplace itself does not create the addiction any more than the supermarket creates food addiction, but it does enable it. Workaholics tend to seek high-stress jobs to keep the adrenaline rush going."

This is true even if they don't work outside the home.

"We're seeing more women workaholics now because women are more visible in the workplace. But it's my belief that even before this trend, workaholics were doing this in the home," says Robinson. "It could be in their parenting to the point where there is nothing else to balance their lives, no hobbies or fun or spirituality, because they spend all their time as the PTA president, running the youth sports league, and being a Scout leader."

Disorders Often Stem From Childhood

Research shows that the seeds of workaholism are often planted in childhood, resulting in low self-esteem that carries into adulthood.

"Many workaholics are the children of alcoholics or come from some other type of dysfunctional family, and work addiction is an attempt to control a situation that is not controllable," he tells WebMD. "Or they tend to be products of what I call 'looking good families' whose parents tend to be perfectionists and expect unreasonable success from their kids. These children grow up thinking that nothing is ever good enough. Some just throw in the towel, but others say, 'I'm going to show I'm the best in everything so [my] parents approve of me.'"

The problem is, perfection is unattainable, whether you're a kid or a successful professional.

"Anyone who carries a mandate for perfection is susceptible to workaholism because it creates a situation where the person never gets to cross the finish line, because it keeps moving farther out," says Saul.

That is why despite logging in mega hours and sacrificing their health and loved ones for their jobs, workaholics are frequently ineffective employees.

Workaholic Styles

"Overall, workaholics tend to be less effective than other workers because it's difficult for them to be team players, they have trouble delegating or entrusting co-workers, or they take on so much that they aren't as organized as others," says Robinson.

In fact, his research indicates four distinct workaholic "working styles":

The bulimic workaholic feels the job must be done perfectly or not at all. Bulimic workaholics often can't get started on projects, and then scramble to complete it by deadline, often frantically working to the point of exhaustion -- with sloppy results.

The relentless workaholic is the adrenaline junkie who often takes on more work than can possibly be done. In an attempt to juggle too many balls, they often work too fast or are too busy for careful, thorough results.

The attention-deficit workaholic often starts with fury, but fails to finish projects -- often because they lose interest for another project. They often savor the "brainstorming" aspects but get easily bored with the necessary details or follow-through.

The savoring workaholic is slow, methodical, and overly scrupulous. They often have trouble letting go of projects and don't work well with others. These are often consummate perfectionists, frequently missing deadlines because "it's not perfect."

Getting Help

What can be done? Counseling is often recommended for workaholics, and support groups, such as Workaholics Anonymous, are beneficial, say the experts.

"It really comes down to recognizing a need for balance in your life," says Robinson. "Working hard is great, but you need to be able to turn if off and savor the other parts of your life -- friends, family, hobbies, and fun."

But many companies often confuse workaholics for hard workers, in essence enabling them on their path to self-destruction.

"I wouldn't say that corporations cause workaholism, but I think they truly support it," says Diane Fassel, PhD, president of Newsmeasures, Inc., a Boulder, Colo., business consulting firm, and the author of Working Ourselves to Death.

"Even though workaholism is the addiction de jour in American corporations, I'm not sure that many companies offer employee-assistance programs for it, as they do for alcohol or drug abuse," she tells WebMD. "Instead they often reward it."

The Debate Over the Addictive Personality and Gender Implications

(from http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/bb/neuro/neuro04/web1/mcurtiss.html)

by MaryBeth Curtiss

Though alcoholism and other damaging addictions are often be traced as symptoms of depression and other emotional distress, the relatively new notion of the "addictive personality" has a significant community of supporters. According to its supporters, the addictive personality is a distinct psychological trait that predisposes particular individuals to addictions. While the nature and the very existence of this trait is still actively debated in the medical, neurobiological and psychology communities, there are definite implications in the brain that contribute to addiction. Also important to this debate are the issues of gender in relation to addiction and how these are and are not compatible with the addictive personality theory.

Addiction, as typically defined, is a reliance on a substance or behavior that the individual has little power to resist. This definition, however, fails to address the neurological aspects of this phenomenon. Dr. Alan Leshner, PhD, of the National Institute on Drug Abuse describes addiction instead as "a brain disease" and "a chronic relapsing disease", in that there are visible alterations in the brains of addicted individuals and these effects are long-lasting within their neurological patterns.(1)Also important in describing addiction is addressing the types of addiction and substance abuse that are often accredited to the addictive personality. There are two primary forms of addiction, one being the substance-based, the second being behavior-based.

The substance-based addictions, such as alcoholism, as well as nicotine, prescription and narcotic addictions, are more easily explained and identified neurologically. Particular drugs, such as crack and heroine cause massive surges in dopamine in the brain, with different sensations ranging from invincibility and strength to euphoric and enlightened states. Use of these substances almost immediately changes particular aspects of the brain's behavior, making most individuals immediately susceptible to future abuse or addiction.

Also common are the behavioral addictions including gambling, shopping, eating, and sexual activity. These addictions are not as easily explained neurologically, but are generally included in the addiction susceptibility characterized by the personality trait. Also common are sorts of combined addictions, that is, addictions that include both substance, as well as behavioral aspects, most commonly the addiction to nicotine, either smoking or chewing. This particular addiction combines a physical addiction to nicotine and a mental facet, the repeated routine of the behavior, such as a cigarette after meals.

Another issue interestingly related to addiction is the relative relationship between these abuses and addictions regarding gender. A collection of recent studies have shown that male adolescents are more active in early drug and alcohol experimentation and that men in general are four times more likely to become dependent on alcohol, twice as likely to routinely use marijuana, and one and a half times more likely to become addicted to cigarettes. Conversely, female adolescents are far more likely to experience the activities associated with behavioral addictions, and women far outnumber men in addictions to eating, binging and purging, thus developing eating disorders at a greater rate.(2)

This stratification may either evidence a key difference in the nature of addictive personalities and a link to gender, or it may discredit the theory as a whole, depending on perspective. It has been shown with other diseases, cancers and genetic traits that particular disorders favor one gender over another, therefore these statistics may show an interesting aspect of the genetic or neurobiological nature of the inherited trait. On the other hand, the variances in the addictions of men and women are often traced to societal values and the images presented to young men and women. In one interesting element of this debate, it seems that the popular image of alcohol consumption among Americans as in mass advertising is one that is largely geared towards men.

Some of the symptoms of alcohol consumption and drunkenness are less acceptable for women, such as uncontrolled behavior, lessened inhibitions and weight gain, while these are more acceptable for men. It also seems that popular images associated with cigarettes have a similarly masculine undertone, as the primary face of the tobacco industry, the "Marlboro Man" embodies popular American manhood like few other icons.

While no one has succeeded in proving the existence of a true addictive personality, many experts now believe that the predisposition to addiction is more accurately a combination of biological, psychological and environmental factors. Certainly, as with all issues of psychology and behavior, the distinct combinations of genetics and inheritance must be countered with an acknowledgment of environmental factors, and the biology of addiction is no exception.

References

1)Sommerset Medical Service Website: The Science of Addiction

2)Hendrick Health System Website: Addiction

by MaryBeth Curtiss

Though alcoholism and other damaging addictions are often be traced as symptoms of depression and other emotional distress, the relatively new notion of the "addictive personality" has a significant community of supporters. According to its supporters, the addictive personality is a distinct psychological trait that predisposes particular individuals to addictions. While the nature and the very existence of this trait is still actively debated in the medical, neurobiological and psychology communities, there are definite implications in the brain that contribute to addiction. Also important to this debate are the issues of gender in relation to addiction and how these are and are not compatible with the addictive personality theory.

Addiction, as typically defined, is a reliance on a substance or behavior that the individual has little power to resist. This definition, however, fails to address the neurological aspects of this phenomenon. Dr. Alan Leshner, PhD, of the National Institute on Drug Abuse describes addiction instead as "a brain disease" and "a chronic relapsing disease", in that there are visible alterations in the brains of addicted individuals and these effects are long-lasting within their neurological patterns.(1)Also important in describing addiction is addressing the types of addiction and substance abuse that are often accredited to the addictive personality. There are two primary forms of addiction, one being the substance-based, the second being behavior-based.

The substance-based addictions, such as alcoholism, as well as nicotine, prescription and narcotic addictions, are more easily explained and identified neurologically. Particular drugs, such as crack and heroine cause massive surges in dopamine in the brain, with different sensations ranging from invincibility and strength to euphoric and enlightened states. Use of these substances almost immediately changes particular aspects of the brain's behavior, making most individuals immediately susceptible to future abuse or addiction.

Also common are the behavioral addictions including gambling, shopping, eating, and sexual activity. These addictions are not as easily explained neurologically, but are generally included in the addiction susceptibility characterized by the personality trait. Also common are sorts of combined addictions, that is, addictions that include both substance, as well as behavioral aspects, most commonly the addiction to nicotine, either smoking or chewing. This particular addiction combines a physical addiction to nicotine and a mental facet, the repeated routine of the behavior, such as a cigarette after meals.

Another issue interestingly related to addiction is the relative relationship between these abuses and addictions regarding gender. A collection of recent studies have shown that male adolescents are more active in early drug and alcohol experimentation and that men in general are four times more likely to become dependent on alcohol, twice as likely to routinely use marijuana, and one and a half times more likely to become addicted to cigarettes. Conversely, female adolescents are far more likely to experience the activities associated with behavioral addictions, and women far outnumber men in addictions to eating, binging and purging, thus developing eating disorders at a greater rate.(2)

This stratification may either evidence a key difference in the nature of addictive personalities and a link to gender, or it may discredit the theory as a whole, depending on perspective. It has been shown with other diseases, cancers and genetic traits that particular disorders favor one gender over another, therefore these statistics may show an interesting aspect of the genetic or neurobiological nature of the inherited trait. On the other hand, the variances in the addictions of men and women are often traced to societal values and the images presented to young men and women. In one interesting element of this debate, it seems that the popular image of alcohol consumption among Americans as in mass advertising is one that is largely geared towards men.

Some of the symptoms of alcohol consumption and drunkenness are less acceptable for women, such as uncontrolled behavior, lessened inhibitions and weight gain, while these are more acceptable for men. It also seems that popular images associated with cigarettes have a similarly masculine undertone, as the primary face of the tobacco industry, the "Marlboro Man" embodies popular American manhood like few other icons.

While no one has succeeded in proving the existence of a true addictive personality, many experts now believe that the predisposition to addiction is more accurately a combination of biological, psychological and environmental factors. Certainly, as with all issues of psychology and behavior, the distinct combinations of genetics and inheritance must be countered with an acknowledgment of environmental factors, and the biology of addiction is no exception.

References

1)Sommerset Medical Service Website: The Science of Addiction

2)Hendrick Health System Website: Addiction

Imaginary Friends: Should You Be Concerned

(from familyresource.com)

By: Armin Brott

Young children often have imaginary friends. Sometimes they're human, other times they're animals, like the life-size rabbit in the old Jimmy Stewart movie, "Harvey." Sometimes the imaginary friend is an occasional visitor, stopping by only once every few days. But other times it may be a child's constant companion. Children may talk to their imaginary friends, draw with them, or even read books to them. And plenty of parents have had to set an extra place at the dinner table for the "friend." So are children's imaginary playmates cause for concern? In most cases, the answer is No. Imaginary friends are a pretty normal part of growing up, especially during the toddler years, and they serve several important functions:

They can be wonderful companions for pretend play, which is an important way to stimulate creativity and imagination. Having an invisible friend can make those long trips to the moon or back in time a little less lonely.

They can act as a child's trusted confidant when there's no one else to tell their secrets to. Even small children have issues that are too private to tell us.

They can help kids figure out the difference between right and wrong. Kids sometimes have a tough time stopping themselves from doing things they know are wrong. Blaming the imaginary friend for eating cookies before dinner is often a sign that the child understands right vs. wrong distinctions but isn't quite ready to assume complete responsibility for her actions.

They can give you some valuable insights into your child's feelings. Listening to your child bravely comfort an invisible friend who's about to get a shot may be a clue that your child is more afraid than she's letting on.

While it's generally perfectly fine to humor your child and go along with her claims about the existence of an imaginary friend, there are a few ground rules:

Don't let the "friend" be your child's only companion. Kids need to socialize with others their own ages. If your child seems to have no other friends or has no interest in being with her peers, talk to your pediatrician.

Don't let your child shift responsibility for everything bad to the friend. Saying that the friend is the one responsible for a nighttime accident is okay. Blaming the friend for a string of bank robberies isn't.

Treat the friend with respect. This means remembering his name, greeting him when you meet, and apologizing when you sit on him.

Don't use the friend to manipulate your child. That means no comments like "Maggie finished her dinner, why don't you finish yours?"

Most kids lose their imaginary friends between their third and fifth birthdays. Sometimes the friends are forgotten, sometimes they're sent on a distant and permanent trip, and other times they "die" in a horrible accident.

A nationally recognized parenting expert, Armin Brott is the author of Father for Life, The Expectant Father: Facts, Tips, and Advice for Dads-to-Be; The New Father: A Dad's Guide to the First Year, A Dad's Guide to the Toddler Years, Throwaway Dads, and The Single Father: A Dad's Guide to Parenting without a Partner. He has written on parenting and fatherhood for the New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post, Newsweek and dozens of other periodicals. He also hosts "Positive Parenting", a nationally distributed, weekly talk show, and lives with his family in Oakland, California. Visit Armin at www.mrdad.com.

By: Armin Brott

Young children often have imaginary friends. Sometimes they're human, other times they're animals, like the life-size rabbit in the old Jimmy Stewart movie, "Harvey." Sometimes the imaginary friend is an occasional visitor, stopping by only once every few days. But other times it may be a child's constant companion. Children may talk to their imaginary friends, draw with them, or even read books to them. And plenty of parents have had to set an extra place at the dinner table for the "friend." So are children's imaginary playmates cause for concern? In most cases, the answer is No. Imaginary friends are a pretty normal part of growing up, especially during the toddler years, and they serve several important functions:

They can be wonderful companions for pretend play, which is an important way to stimulate creativity and imagination. Having an invisible friend can make those long trips to the moon or back in time a little less lonely.

They can act as a child's trusted confidant when there's no one else to tell their secrets to. Even small children have issues that are too private to tell us.

They can help kids figure out the difference between right and wrong. Kids sometimes have a tough time stopping themselves from doing things they know are wrong. Blaming the imaginary friend for eating cookies before dinner is often a sign that the child understands right vs. wrong distinctions but isn't quite ready to assume complete responsibility for her actions.

They can give you some valuable insights into your child's feelings. Listening to your child bravely comfort an invisible friend who's about to get a shot may be a clue that your child is more afraid than she's letting on.

While it's generally perfectly fine to humor your child and go along with her claims about the existence of an imaginary friend, there are a few ground rules:

Don't let the "friend" be your child's only companion. Kids need to socialize with others their own ages. If your child seems to have no other friends or has no interest in being with her peers, talk to your pediatrician.

Don't let your child shift responsibility for everything bad to the friend. Saying that the friend is the one responsible for a nighttime accident is okay. Blaming the friend for a string of bank robberies isn't.

Treat the friend with respect. This means remembering his name, greeting him when you meet, and apologizing when you sit on him.

Don't use the friend to manipulate your child. That means no comments like "Maggie finished her dinner, why don't you finish yours?"

Most kids lose their imaginary friends between their third and fifth birthdays. Sometimes the friends are forgotten, sometimes they're sent on a distant and permanent trip, and other times they "die" in a horrible accident.

A nationally recognized parenting expert, Armin Brott is the author of Father for Life, The Expectant Father: Facts, Tips, and Advice for Dads-to-Be; The New Father: A Dad's Guide to the First Year, A Dad's Guide to the Toddler Years, Throwaway Dads, and The Single Father: A Dad's Guide to Parenting without a Partner. He has written on parenting and fatherhood for the New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post, Newsweek and dozens of other periodicals. He also hosts "Positive Parenting", a nationally distributed, weekly talk show, and lives with his family in Oakland, California. Visit Armin at www.mrdad.com.

'Pretend' friends, real benefits (USA Today)

USA Today

Posted 12/19/2004 9:34 PM

'Pretend' friends, real benefits

By Marilyn Elias, USA TODAY

Children get by with the help of their friends, and imaginary friends might be some of the most helpful, suggests a study that challenges the traditional view that well-adjusted kids give up pretend pals after preschool.

About two-thirds of children have played with imaginary companions by age 7, and one-third still have them at 7, according to the first study that follows children's pretend play partners from age 3 through early elementary school.

Kids who have imaginary friends feel just as competent and popular as those who don't, and their personalities are no different, says Marjorie Taylor of the University of Oregon. She reported the study along with Stephanie Carlson in the latest issue of Developmental Psychology.

"Imaginary companions have had a bad rap from psychologists for a long time," Carlson says. Jean Piaget, an influential Swiss psychologist whose theories on early childhood development took hold in the 1960s, believed that these friends reflect immature thinking and should vanish by the time a child starts school.

But there has been little research on the purpose of pretend pals and whether school-age kids do shed them, Taylor says. Her study of 100 children finds that imaginary friends come and go. Some are invisible humans, the children say. The talking buddy also can be an animal, a doll or a GI Joe.

Just like any good friend, the imaginary friend offers companionship and entertainment and can help buck children up for tough times, researchers say. "It makes you feel brave to walk by that scary dog next door if you have an invisible tiger by your side," Taylor says.

Kids also use invented friends to practice conflict resolution, Carlson says. Parents who eavesdrop on pretend play can open a window into their child's world, says Barbara Willer of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. "It gives you insight into their fears and challenges."

One little girl told the researchers she has two imaginary friends: One helps her wait patiently until the busy one shows up. "You have to wonder if she might be talking about her parents," Taylor says.

In her study, 27% of children described pretend pals their parents didn't know about, she says. If they know, reactions vary widely. "We've seen everything from parents who are excited and proud, even kind of implying, 'My child has a better friend than your child,' to a fundamentalist Christian who brought a Bible to the lab and said she was praying every day for the devil to leave her child," Taylor says.

Pretend friends rarely are a sign of emotional problems, she says. If a child claims a friend is controlling her and making her do things she doesn't want to do, parents should seek psychological help, Taylor says. But if a child isn't depressed and has real-life friends too, pretend pals shouldn't cause concern.

In fact, parents should look for day care and preschool programs that allow time for imaginative play so children can interact with pretend figures, Willer says. "Even if parents discourage it, it's going to happen."

Posted 12/19/2004 9:34 PM

'Pretend' friends, real benefits

By Marilyn Elias, USA TODAY

Children get by with the help of their friends, and imaginary friends might be some of the most helpful, suggests a study that challenges the traditional view that well-adjusted kids give up pretend pals after preschool.

About two-thirds of children have played with imaginary companions by age 7, and one-third still have them at 7, according to the first study that follows children's pretend play partners from age 3 through early elementary school.

Kids who have imaginary friends feel just as competent and popular as those who don't, and their personalities are no different, says Marjorie Taylor of the University of Oregon. She reported the study along with Stephanie Carlson in the latest issue of Developmental Psychology.

"Imaginary companions have had a bad rap from psychologists for a long time," Carlson says. Jean Piaget, an influential Swiss psychologist whose theories on early childhood development took hold in the 1960s, believed that these friends reflect immature thinking and should vanish by the time a child starts school.

But there has been little research on the purpose of pretend pals and whether school-age kids do shed them, Taylor says. Her study of 100 children finds that imaginary friends come and go. Some are invisible humans, the children say. The talking buddy also can be an animal, a doll or a GI Joe.

Just like any good friend, the imaginary friend offers companionship and entertainment and can help buck children up for tough times, researchers say. "It makes you feel brave to walk by that scary dog next door if you have an invisible tiger by your side," Taylor says.

Kids also use invented friends to practice conflict resolution, Carlson says. Parents who eavesdrop on pretend play can open a window into their child's world, says Barbara Willer of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. "It gives you insight into their fears and challenges."

One little girl told the researchers she has two imaginary friends: One helps her wait patiently until the busy one shows up. "You have to wonder if she might be talking about her parents," Taylor says.

In her study, 27% of children described pretend pals their parents didn't know about, she says. If they know, reactions vary widely. "We've seen everything from parents who are excited and proud, even kind of implying, 'My child has a better friend than your child,' to a fundamentalist Christian who brought a Bible to the lab and said she was praying every day for the devil to leave her child," Taylor says.

Pretend friends rarely are a sign of emotional problems, she says. If a child claims a friend is controlling her and making her do things she doesn't want to do, parents should seek psychological help, Taylor says. But if a child isn't depressed and has real-life friends too, pretend pals shouldn't cause concern.

In fact, parents should look for day care and preschool programs that allow time for imaginative play so children can interact with pretend figures, Willer says. "Even if parents discourage it, it's going to happen."

6-Year-Old Commits Suicide (N.Y. Times)

Published: June 17, 1993

A 6-year-old girl was killed today when she stepped in front of a train, telling two siblings and a cousin that she wanted "to become an angel and be with her mother." The girl was identified as Jackie Johnson; the authorities said her mother, Carla Johnson, had a terminal illness. Jackie's death was ruled a suicide.

(from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9F0CEFDB1631F934A25755C0A965958260)

Details about Jackie and youth suicides can be found in the book Lay My Burden Down viewable as a pdf file by clicking:

http://books.google.com/books?id=9hu0b98irW8C&pg=PA43&lpg=PA43&dq=jackie+johnson+suicide&source=web&ots=Y8NKjRm3mw&sig=lX31pvgP_7LEja-oY1_Y0f2ibx8#PPA42,M1

A 6-year-old girl was killed today when she stepped in front of a train, telling two siblings and a cousin that she wanted "to become an angel and be with her mother." The girl was identified as Jackie Johnson; the authorities said her mother, Carla Johnson, had a terminal illness. Jackie's death was ruled a suicide.

(from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9F0CEFDB1631F934A25755C0A965958260)

Details about Jackie and youth suicides can be found in the book Lay My Burden Down viewable as a pdf file by clicking:

http://books.google.com/books?id=9hu0b98irW8C&pg=PA43&lpg=PA43&dq=jackie+johnson+suicide&source=web&ots=Y8NKjRm3mw&sig=lX31pvgP_7LEja-oY1_Y0f2ibx8#PPA42,M1

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS: Suicide and Suicide Attempts in Adolescents

(excerpts from http://aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;105/4/871)

Suicide is the third leading cause of death for adolescents 15 to 19 years old.

The number of adolescent deaths from suicide in the United States has increased dramatically during the past few decades. In 1997, there were 4186 suicides among people 15 to 24 years old, 1802 suicides among those 15 to 19 years old, and 2384 among those 20 to 24 years old.1 In 1997, 13% of all deaths in the 15- through 24-year-old age group were attributable to suicide.1 The true number of deaths from suicide actually may be higher, because some of these deaths are recorded as "accidental."3

From 1950 to 1990, the suicide rate for adolescents in the 15- to 19-year-old group increased by 300%.4 Adolescent males 15 to 19 years old had a rate 6 times greater than the rate for females.1 The ratio of attempted suicides to completed suicides among adolescents is estimated to be 50:1 to 100:1, and the incidence of unsuccessful suicide attempts is higher among females than among males.5 Suicide affects young people from all races and socioeconomic groups, although some groups seem to have higher rates than others. Native American males have the highest suicide rate, African American women the lowest. A statewide survey of students in grades 7 through 12 found that 28.1% of bisexual and homosexual males and 20.5% of bisexual and homosexual females had reported attempting suicide.6 The National Youth Risk Behavior Survey of students in grades 9 through 12 indicated that nearly one fourth (24.1%) of students had seriously considered attempting suicide during the 12 months preceding the survey, 17.7% had made a specific plan, and 8.7% had made an attempt.7

Firearms, used in >67% of suicides, are the leading cause of death for males and females who commit suicide.8 More than 90% of suicide attempts involving a firearm are fatal because there is little chance for rescue. Firearms in the home, regardless of whether they are kept unloaded or stored locked up, are associated with a higher risk for adolescent suicide.9,10 Parents must be warned about the lethality of firearms in the home and be advised strongly to remove them from the premises.11 Ingestion of pills is the most common method among adolescents who attempt suicide.

Youth, who seem to be at much greater risk from media exposure than adults, may imitate suicidal behavior seen on television.12 Media coverage of a teenage suicide may lead to cluster suicides, additional deaths from suicides in youths within a 1- to 2-week period afterward.12-14

ADOLESCENTS AT INCREASED RISK

Although no specific tests are capable of identifying suicidal persons, specific risk factors exist.

Adolescents at higher risk commonly have a history of depression, a previous suicide attempt, a family history of psychiatric disorders (especially depression and suicidal behavior), family disruption, and certain chronic or debilitating physical disorders or psychiatric illness.15 Alcohol use and alcoholism indicate high risk for suicide.16 Alcohol use has been associated with 50% of suicides.17 Living out of the home (in a correctional facility or group home) and a history of physical or sexual abuse are additional factors more commonly found in adolescents who exhibit suicidal behavior.18 Psychosocial problems and stresses, such as conflicts with parents, breakup of a relationship, school difficulties or failure, legal difficulties, social isolation, and physical ailments (including hypochondriacal preoccupation), commonly are reported or observed in young people who attempt suicide. These precipitating factors often are cited by youths as reasons for attempting suicide. Gay and bisexual adolescents have been reported to exhibit high rates of depression and have been reported to have rates of suicidal ideation and attempts 3 times higher than other adolescents. Studies of twins show that monozygotic twins show significantly higher concordance for suicide than dizygotic twins.16 Long-term high levels of community violence may contribute to emotional and conduct problems and add to the risk of suicide for exposed youth.19 Adolescent and parent questionnaires that cover those risk factors listed above, may be useful in the office setting to assist in obtaining a complete history.20

Serious depression in adolescents may manifest in several ways. For some adolescents, symptoms may be similar to those in adults, with signs, such as depressed mood almost every day, crying spells or inability to cry, discouragement, irritability, a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness, negative expectations of self and the environment, low self-esteem, isolation, a feeling of helplessness, markedly diminished interest or pleasure in most activities, significant weight loss or weight gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, and diminished ability to think or concentrate.21 However, it is more common for an adolescent with serious depression to exhibit psychosomatic symptoms or behavioral problems. Such a teenager may seek care for recurrent or persistent complaints, such as abdominal pain, chest pain, headache, lethargy, weight loss, dizziness and syncope, or other nonspecific symptoms.22 Behavioral problems that may be manifestations of masked depression include truancy, deterioration in academic performance, running away from home, defiance of authorities, self-destructive behavior, vandalism, alcohol and other drug abuse, sexual acting out, and delinquency.23 Episodic despondency leading to self-destructive acts can occur in any adolescent, including high achievers. These adolescents may believe that they have failed or disappointed their parents and family and perceive suicide as their only option. Other adolescents may believe that suicide is a better option than life as they experience it.

TABLE 1 Examples of Adolescents at Low, Moderate, and High Risk for Suicide

Low risk:

Took 5 ibuprofen tablets after argument with girlfriend

Impulsive; told mother 15 minutes after taking pills

No serious problems at home or school

Occasionally feels "down" but has no history of depression or serious emotional problems

Has a number of good friends

Wants help resolving problems and is no longer considering suicide after interview

Moderate risk:

Suicidal ideation precipitated by recurrent fighting with parents and failing grades in school

Wants to "get back" at parents

Cut both wrists while at home alone; called friend 30 minutes later

Parents separated, changed school this semester, history of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Symptoms of depression for the last 2 months, difficulty controlling temper

Binge drinking on the weekends

Answers all the questions during the interview, agrees to see a therapist if parents get counseling, will contact the interviewer if suicidal thoughts return

High risk:

Thrown out of house by parents for smoking marijuana at school, girlfriend broke up with him last night, best friend killed in auto crash last month

Wants to be dead; sees no purpose in living

Took father's gun; is going to shoot himself where "no one can find me"

Gets drunk every weekend and uses marijuana daily

Hates parents and school; has run away from home twice and has not gone to school for 6 weeks

Hospitalized in the past because he "lost it"

Does not want to answer many of the questions during the interview and hates "shrinks"

Suicide is the third leading cause of death for adolescents 15 to 19 years old.

The number of adolescent deaths from suicide in the United States has increased dramatically during the past few decades. In 1997, there were 4186 suicides among people 15 to 24 years old, 1802 suicides among those 15 to 19 years old, and 2384 among those 20 to 24 years old.1 In 1997, 13% of all deaths in the 15- through 24-year-old age group were attributable to suicide.1 The true number of deaths from suicide actually may be higher, because some of these deaths are recorded as "accidental."3

From 1950 to 1990, the suicide rate for adolescents in the 15- to 19-year-old group increased by 300%.4 Adolescent males 15 to 19 years old had a rate 6 times greater than the rate for females.1 The ratio of attempted suicides to completed suicides among adolescents is estimated to be 50:1 to 100:1, and the incidence of unsuccessful suicide attempts is higher among females than among males.5 Suicide affects young people from all races and socioeconomic groups, although some groups seem to have higher rates than others. Native American males have the highest suicide rate, African American women the lowest. A statewide survey of students in grades 7 through 12 found that 28.1% of bisexual and homosexual males and 20.5% of bisexual and homosexual females had reported attempting suicide.6 The National Youth Risk Behavior Survey of students in grades 9 through 12 indicated that nearly one fourth (24.1%) of students had seriously considered attempting suicide during the 12 months preceding the survey, 17.7% had made a specific plan, and 8.7% had made an attempt.7

Firearms, used in >67% of suicides, are the leading cause of death for males and females who commit suicide.8 More than 90% of suicide attempts involving a firearm are fatal because there is little chance for rescue. Firearms in the home, regardless of whether they are kept unloaded or stored locked up, are associated with a higher risk for adolescent suicide.9,10 Parents must be warned about the lethality of firearms in the home and be advised strongly to remove them from the premises.11 Ingestion of pills is the most common method among adolescents who attempt suicide.

Youth, who seem to be at much greater risk from media exposure than adults, may imitate suicidal behavior seen on television.12 Media coverage of a teenage suicide may lead to cluster suicides, additional deaths from suicides in youths within a 1- to 2-week period afterward.12-14

ADOLESCENTS AT INCREASED RISK

Although no specific tests are capable of identifying suicidal persons, specific risk factors exist.

Adolescents at higher risk commonly have a history of depression, a previous suicide attempt, a family history of psychiatric disorders (especially depression and suicidal behavior), family disruption, and certain chronic or debilitating physical disorders or psychiatric illness.15 Alcohol use and alcoholism indicate high risk for suicide.16 Alcohol use has been associated with 50% of suicides.17 Living out of the home (in a correctional facility or group home) and a history of physical or sexual abuse are additional factors more commonly found in adolescents who exhibit suicidal behavior.18 Psychosocial problems and stresses, such as conflicts with parents, breakup of a relationship, school difficulties or failure, legal difficulties, social isolation, and physical ailments (including hypochondriacal preoccupation), commonly are reported or observed in young people who attempt suicide. These precipitating factors often are cited by youths as reasons for attempting suicide. Gay and bisexual adolescents have been reported to exhibit high rates of depression and have been reported to have rates of suicidal ideation and attempts 3 times higher than other adolescents. Studies of twins show that monozygotic twins show significantly higher concordance for suicide than dizygotic twins.16 Long-term high levels of community violence may contribute to emotional and conduct problems and add to the risk of suicide for exposed youth.19 Adolescent and parent questionnaires that cover those risk factors listed above, may be useful in the office setting to assist in obtaining a complete history.20

Serious depression in adolescents may manifest in several ways. For some adolescents, symptoms may be similar to those in adults, with signs, such as depressed mood almost every day, crying spells or inability to cry, discouragement, irritability, a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness, negative expectations of self and the environment, low self-esteem, isolation, a feeling of helplessness, markedly diminished interest or pleasure in most activities, significant weight loss or weight gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, and diminished ability to think or concentrate.21 However, it is more common for an adolescent with serious depression to exhibit psychosomatic symptoms or behavioral problems. Such a teenager may seek care for recurrent or persistent complaints, such as abdominal pain, chest pain, headache, lethargy, weight loss, dizziness and syncope, or other nonspecific symptoms.22 Behavioral problems that may be manifestations of masked depression include truancy, deterioration in academic performance, running away from home, defiance of authorities, self-destructive behavior, vandalism, alcohol and other drug abuse, sexual acting out, and delinquency.23 Episodic despondency leading to self-destructive acts can occur in any adolescent, including high achievers. These adolescents may believe that they have failed or disappointed their parents and family and perceive suicide as their only option. Other adolescents may believe that suicide is a better option than life as they experience it.

TABLE 1 Examples of Adolescents at Low, Moderate, and High Risk for Suicide

Low risk:

Took 5 ibuprofen tablets after argument with girlfriend

Impulsive; told mother 15 minutes after taking pills

No serious problems at home or school

Occasionally feels "down" but has no history of depression or serious emotional problems

Has a number of good friends

Wants help resolving problems and is no longer considering suicide after interview

Moderate risk:

Suicidal ideation precipitated by recurrent fighting with parents and failing grades in school

Wants to "get back" at parents

Cut both wrists while at home alone; called friend 30 minutes later

Parents separated, changed school this semester, history of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Symptoms of depression for the last 2 months, difficulty controlling temper

Binge drinking on the weekends

Answers all the questions during the interview, agrees to see a therapist if parents get counseling, will contact the interviewer if suicidal thoughts return

High risk:

Thrown out of house by parents for smoking marijuana at school, girlfriend broke up with him last night, best friend killed in auto crash last month

Wants to be dead; sees no purpose in living

Took father's gun; is going to shoot himself where "no one can find me"

Gets drunk every weekend and uses marijuana daily

Hates parents and school; has run away from home twice and has not gone to school for 6 weeks

Hospitalized in the past because he "lost it"

Does not want to answer many of the questions during the interview and hates "shrinks"

N.Y. Times Review

November 21, 2005

THEATER REVIEW

'MR. MARMALADE'

A 4-Year-Old Who Needs a Divorce

By CHARLES ISHERWOOD

With imaginary friends like Mr. Marmalade, the creepy title character in a new play by Noah Haidle, what 4-year-old needs enemies? That more or less sums up the joke that's stretched to fill 90 minutes in this zany comedy about emotionally disturbed children (yes, you read that right), a Roundabout Theater Company production that opened last night at the Laura Pels Theater.

In "Mr. Marmalade," Mr. Haidle, a playwright new to Off Broadway, aims to unsettle and delight in equal measure. The play conjures in bright Crayola colors the precociously adult mindscape of little Lucy (played by the adult actress Mamie Gummer), a pigtailed New Jersey tot whose fantasy companion comes accessorized with personal assistant, bipolar disorder and cocaine problem. But "Mr. Marmalade," which stars Michael C. Hall of "Six Feet Under" fame as the sinister title character, never truly capitalizes on its provocative conceit. Mr. Haidle chooses instead to draw us a scary but ultimately hollow cartoon.

His thesis: a toxic combination of neglect and exposure to the noisy dysfunction in the cultural ether could so warp a tyke's psyche that she dreams up a pal who prefers sex toys to tea parties. Gasps of uncomfortable laughter arise from the audience as the bewildered Lucy negotiates the mood swings of her now-cuddly, now-abusive friend, aping the enabling instincts of her elders. Besieged by loneliness, she seeks his love even after benign neglect - a delayed brunch date - gives way to physical and emotional violence. In a world permeated with chatter about sex and commitment and issues of self-esteem, the play argues, no child is left behind for long.

But Lucy's interior world is so patently incredible as the creation of a 4-year-old mind, however marinated in the scream-fests of daytime television and episodes of "Law & Order: SVU," that the author never really even dips his toe into the painful emotional undercurrents beneath the play's antic comic surface. Instead, he settles too easily and too consistently for cheap laughs.

Lucy's lexicon is too sophisticated to suggest random imprinting from endless hours of television consumption, to begin with. (A recliner and a jumbo tube are tellingly parked dead center in Allen Moyer's set, which is ringed in loud wallpaper.) With her knowledge of interns and brunch and the menu at Nobu, Lucy's vocabulary is littered with such references planted to serve as punch lines. How to explain this urbanity, when her distracted single mom appears to work as a waitress in a diner? (Never mind the distasteful implication that neglectful mothering is endemic to the working classes.)

Lucy also displays a knack for quippery to match her smooth talk. The slatternly baby sitter, awaiting the arrival of her boyfriend, asks, "How do I look?" "Easy," squeaks Lucy, her timing flawless. Far from languishing in lonely obscurity, with only Mr. M, his assistant (David Costabile) and her one nonfictional friend, a suicidal 5-year-old named Larry (Pablo Schreiber), for company, this comic prodigy might easily have skipped preschool and jumped straight to a staff job on Fox's late, lamented "Arrested Development."

It is obviously true that young children can latch on to stray words and ideas seeping down from exchanges between careless adults. And there is, of course, a long history of literature that marries the anxieties of the adult world and the phantasms of childhood daydreams, going as far back as Lewis Carroll's plucky Alice. Likewise, playwrights like Christopher Durang, Craig Lucas and David Lindsay-Abaire have successfully spun tales of violent emotional warfare trimmed with wacky comic flourishes.

But Mr. Haidle has invited us down a rabbit hole that really leads nowhere. In between the tea parties and naughty games of doctor, Lucy carries on so many complex conversations about concepts (suicide, infidelity) blatantly beyond a 4-year-old's intellectual capacity that her nightmare world retains no grip on our imaginations or our emotions. It is too palpably shaped by the playwright, not by his character. (The snarky, portentous epigraphs for each scene do not help: "III. Concerning countless more hardships which Lucy endured with regard to her imaginary friends, if you can even call them that," runs one.)

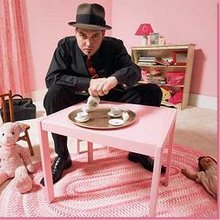

The director, Michael Greif, and the actors bring a frenzied sense of fun to the play's lighter moments. It's hard to resist the sugar-shock food fight that Larry and Lucy embark on during a respite from their more sinister games, with Larry's somewhat more anodyne imaginary companions, a potty-mouthed cactus and sunflower, joining in. As Mr. Marmalade, Mr. Hall is flesh-crawlingly watchable as he twitches suddenly between roles as teddy bear in a business suit and abusive beast. In her Off Broadway debut, Ms. Gummer (a daughter of Meryl Streep) pouts and chirps childishly and effectively, even if she cannot mask the contradictions of her character.

But the gruesome excesses of Mr. Haidle's plot strike too many unearned sour notes. In exaggerating Lucy's self-inflicted emotional torture to spark spasms of nervous laughter, Mr. Haidle sacrifices the chance to explore his dark subject matter honestly. And you don't have to be a prig to wish that a playwright dealing with the idea of children's suffering would demonstrate an awareness that the subject is sadly not as far-fetched as the loopy tone would suggest.

Mr. Haidle does strive to end the play on a note of tentative hope. After Lucy has finally exorcised her demon, she is seen frolicking outdoors with Larry in a merry game of dodge ball, free at last from the terrors of her diseased imagination. But hold on, Mr. Haidle - dodge ball as a healing balm for toddler angst? In my experience, that infernal game was more likely to be the cause of trauma, not the cure for it. Heck, I've still got the emotional scars to prove it.

"Mr. Marmalade" continues at the Laura Pels Theater, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theater, 111 West 46th Street, Manhattan, through Jan. 29, 2006; (212) 719-1300.

THEATER REVIEW

'MR. MARMALADE'

A 4-Year-Old Who Needs a Divorce

By CHARLES ISHERWOOD

With imaginary friends like Mr. Marmalade, the creepy title character in a new play by Noah Haidle, what 4-year-old needs enemies? That more or less sums up the joke that's stretched to fill 90 minutes in this zany comedy about emotionally disturbed children (yes, you read that right), a Roundabout Theater Company production that opened last night at the Laura Pels Theater.

In "Mr. Marmalade," Mr. Haidle, a playwright new to Off Broadway, aims to unsettle and delight in equal measure. The play conjures in bright Crayola colors the precociously adult mindscape of little Lucy (played by the adult actress Mamie Gummer), a pigtailed New Jersey tot whose fantasy companion comes accessorized with personal assistant, bipolar disorder and cocaine problem. But "Mr. Marmalade," which stars Michael C. Hall of "Six Feet Under" fame as the sinister title character, never truly capitalizes on its provocative conceit. Mr. Haidle chooses instead to draw us a scary but ultimately hollow cartoon.

His thesis: a toxic combination of neglect and exposure to the noisy dysfunction in the cultural ether could so warp a tyke's psyche that she dreams up a pal who prefers sex toys to tea parties. Gasps of uncomfortable laughter arise from the audience as the bewildered Lucy negotiates the mood swings of her now-cuddly, now-abusive friend, aping the enabling instincts of her elders. Besieged by loneliness, she seeks his love even after benign neglect - a delayed brunch date - gives way to physical and emotional violence. In a world permeated with chatter about sex and commitment and issues of self-esteem, the play argues, no child is left behind for long.

But Lucy's interior world is so patently incredible as the creation of a 4-year-old mind, however marinated in the scream-fests of daytime television and episodes of "Law & Order: SVU," that the author never really even dips his toe into the painful emotional undercurrents beneath the play's antic comic surface. Instead, he settles too easily and too consistently for cheap laughs.

Lucy's lexicon is too sophisticated to suggest random imprinting from endless hours of television consumption, to begin with. (A recliner and a jumbo tube are tellingly parked dead center in Allen Moyer's set, which is ringed in loud wallpaper.) With her knowledge of interns and brunch and the menu at Nobu, Lucy's vocabulary is littered with such references planted to serve as punch lines. How to explain this urbanity, when her distracted single mom appears to work as a waitress in a diner? (Never mind the distasteful implication that neglectful mothering is endemic to the working classes.)

Lucy also displays a knack for quippery to match her smooth talk. The slatternly baby sitter, awaiting the arrival of her boyfriend, asks, "How do I look?" "Easy," squeaks Lucy, her timing flawless. Far from languishing in lonely obscurity, with only Mr. M, his assistant (David Costabile) and her one nonfictional friend, a suicidal 5-year-old named Larry (Pablo Schreiber), for company, this comic prodigy might easily have skipped preschool and jumped straight to a staff job on Fox's late, lamented "Arrested Development."

It is obviously true that young children can latch on to stray words and ideas seeping down from exchanges between careless adults. And there is, of course, a long history of literature that marries the anxieties of the adult world and the phantasms of childhood daydreams, going as far back as Lewis Carroll's plucky Alice. Likewise, playwrights like Christopher Durang, Craig Lucas and David Lindsay-Abaire have successfully spun tales of violent emotional warfare trimmed with wacky comic flourishes.

But Mr. Haidle has invited us down a rabbit hole that really leads nowhere. In between the tea parties and naughty games of doctor, Lucy carries on so many complex conversations about concepts (suicide, infidelity) blatantly beyond a 4-year-old's intellectual capacity that her nightmare world retains no grip on our imaginations or our emotions. It is too palpably shaped by the playwright, not by his character. (The snarky, portentous epigraphs for each scene do not help: "III. Concerning countless more hardships which Lucy endured with regard to her imaginary friends, if you can even call them that," runs one.)

The director, Michael Greif, and the actors bring a frenzied sense of fun to the play's lighter moments. It's hard to resist the sugar-shock food fight that Larry and Lucy embark on during a respite from their more sinister games, with Larry's somewhat more anodyne imaginary companions, a potty-mouthed cactus and sunflower, joining in. As Mr. Marmalade, Mr. Hall is flesh-crawlingly watchable as he twitches suddenly between roles as teddy bear in a business suit and abusive beast. In her Off Broadway debut, Ms. Gummer (a daughter of Meryl Streep) pouts and chirps childishly and effectively, even if she cannot mask the contradictions of her character.

But the gruesome excesses of Mr. Haidle's plot strike too many unearned sour notes. In exaggerating Lucy's self-inflicted emotional torture to spark spasms of nervous laughter, Mr. Haidle sacrifices the chance to explore his dark subject matter honestly. And you don't have to be a prig to wish that a playwright dealing with the idea of children's suffering would demonstrate an awareness that the subject is sadly not as far-fetched as the loopy tone would suggest.

Mr. Haidle does strive to end the play on a note of tentative hope. After Lucy has finally exorcised her demon, she is seen frolicking outdoors with Larry in a merry game of dodge ball, free at last from the terrors of her diseased imagination. But hold on, Mr. Haidle - dodge ball as a healing balm for toddler angst? In my experience, that infernal game was more likely to be the cause of trauma, not the cure for it. Heck, I've still got the emotional scars to prove it.

"Mr. Marmalade" continues at the Laura Pels Theater, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theater, 111 West 46th Street, Manhattan, through Jan. 29, 2006; (212) 719-1300.

Comedy with a side of darkness: At 28, playwright Haidle strikes a 'daring' balance

(from The Boston Globe)

By Mark Feeney, Globe Staff

March 28, 2007

Noah Haidle grew up assuming he'd be a scientist. So when at 17 he decided he wanted to be a playwright, instead, he used the same method to pursue his goal a scientist would: induction. Yet rather than amassing data by conducting experiments in a laboratory, Haidle amassed data through reading every play he could get his hands on.

"It just became a kind of private obsession," Haidle said last week, sitting outside Wimberly Theatre at the Boston Center for the Arts. The Huntington Theatre will be mounting the world premiere there of Haidle's play "Persephone ." It opens Friday.

"The idea was, if I ingest enough, if I read enough -- because my access to theater was largely through reading -- sooner or later I'll be able to synthesize something of my own. So the bet has kind of paid off."

Paid off handsomely, it would seem. At 28, Haidle (pronounced HIGH-del), is one of the foremost playwrights of his generation. Productions of such darkly comic plays as "Mr. Marmalade ," in which a 4-year-old has an abusive yuppie as an imaginary friend, or "Vigils, " about a woman who keeps the soul of her dead husband in a box, have brought Haidle praise and generated controversy.

Haidle "is the most original young playwright writing today -- and the most daring," Nicholas Martin , who's directing "Persephone," said in a telephone interview.

"You know how a lot of young playwrights have a lot of gratuitous violence or atrocity in their plays, and you think, why? When Noah uses such things, they're not sensationalist. They're a kind of moralistic point of view, though he'd hate me for saying that. He's what I call a foul-mouthed moralist."

"Persephone" has its share of shocking moments, involving acts of violence and sex (the latter both consensual and not). None of those acts directly involves the protagonist, though. Not much can, other than the indignities deposited by the occasional passing pigeon. She's a statue of the Greek goddess Demeter , played by Marilyn Dodds Frank .

Demeter, the Greek goddess of the harvest (whose daughter was Persephone), is the very still point in a sadly turning world. That world reaches from an artist's studio in Florence in 1507, where a sculptor is putting the finishing touches to Demeter, to a New York park 500 years later, where she sits on a begrimed pedestal.

"I don't expect everyone will like 'Persephone,' " Martin said, "but I hope they understand the right things about it. That is, it comes out for humanity -- even though a statue represents humanity in it. I've tried to stage what I call the atrocities with a little bit of poetry, but it's very tricky that line. That's Noah's line, actually, you have to make it ugly because that's the point of the play."

Some of "Persephone" has the jokey-ness of shtick. Other parts are anything but jokey. Haidle says that determinedly uneasy blend is in the nature of how he writes. Laughter and darkness intertwine in his work, eluding any simple designation of comedy and tragedy.

"I've never tried to write a comedy," Haidle declared. "I've never said, let's make this funny -- or no laughs, this is very serious, a tragedy, no laughter. It just happens that way. "

The basic premise -- an immobilized woman directly addressing the audience -- recalls Samuel Beckett's "Happy Days. " Haidle said there was no conscious connection to Beckett, but that he takes any comparisons, however tenuous, as a great compliment.

"The problem with Mr. Beckett is everything he did is so original," Haidle said. "He's my favorite writer of all time -- prose, poetry, plays. I think I've read everything. I'm actually going to Paris after this production just to walk around where he walked, just go see his apartment and stuff. I'm absolutely obsessed with him."