November 21, 2005

THEATER REVIEW

'MR. MARMALADE'

A 4-Year-Old Who Needs a Divorce

By CHARLES ISHERWOOD

With imaginary friends like Mr. Marmalade, the creepy title character in a new play by Noah Haidle, what 4-year-old needs enemies? That more or less sums up the joke that's stretched to fill 90 minutes in this zany comedy about emotionally disturbed children (yes, you read that right), a Roundabout Theater Company production that opened last night at the Laura Pels Theater.

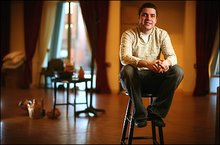

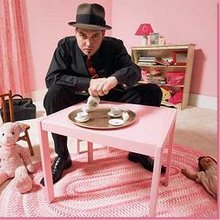

In "Mr. Marmalade," Mr. Haidle, a playwright new to Off Broadway, aims to unsettle and delight in equal measure. The play conjures in bright Crayola colors the precociously adult mindscape of little Lucy (played by the adult actress Mamie Gummer), a pigtailed New Jersey tot whose fantasy companion comes accessorized with personal assistant, bipolar disorder and cocaine problem. But "Mr. Marmalade," which stars Michael C. Hall of "Six Feet Under" fame as the sinister title character, never truly capitalizes on its provocative conceit. Mr. Haidle chooses instead to draw us a scary but ultimately hollow cartoon.

His thesis: a toxic combination of neglect and exposure to the noisy dysfunction in the cultural ether could so warp a tyke's psyche that she dreams up a pal who prefers sex toys to tea parties. Gasps of uncomfortable laughter arise from the audience as the bewildered Lucy negotiates the mood swings of her now-cuddly, now-abusive friend, aping the enabling instincts of her elders. Besieged by loneliness, she seeks his love even after benign neglect - a delayed brunch date - gives way to physical and emotional violence. In a world permeated with chatter about sex and commitment and issues of self-esteem, the play argues, no child is left behind for long.

But Lucy's interior world is so patently incredible as the creation of a 4-year-old mind, however marinated in the scream-fests of daytime television and episodes of "Law & Order: SVU," that the author never really even dips his toe into the painful emotional undercurrents beneath the play's antic comic surface. Instead, he settles too easily and too consistently for cheap laughs.

Lucy's lexicon is too sophisticated to suggest random imprinting from endless hours of television consumption, to begin with. (A recliner and a jumbo tube are tellingly parked dead center in Allen Moyer's set, which is ringed in loud wallpaper.) With her knowledge of interns and brunch and the menu at Nobu, Lucy's vocabulary is littered with such references planted to serve as punch lines. How to explain this urbanity, when her distracted single mom appears to work as a waitress in a diner? (Never mind the distasteful implication that neglectful mothering is endemic to the working classes.)

Lucy also displays a knack for quippery to match her smooth talk. The slatternly baby sitter, awaiting the arrival of her boyfriend, asks, "How do I look?" "Easy," squeaks Lucy, her timing flawless. Far from languishing in lonely obscurity, with only Mr. M, his assistant (David Costabile) and her one nonfictional friend, a suicidal 5-year-old named Larry (Pablo Schreiber), for company, this comic prodigy might easily have skipped preschool and jumped straight to a staff job on Fox's late, lamented "Arrested Development."

It is obviously true that young children can latch on to stray words and ideas seeping down from exchanges between careless adults. And there is, of course, a long history of literature that marries the anxieties of the adult world and the phantasms of childhood daydreams, going as far back as Lewis Carroll's plucky Alice. Likewise, playwrights like Christopher Durang, Craig Lucas and David Lindsay-Abaire have successfully spun tales of violent emotional warfare trimmed with wacky comic flourishes.

But Mr. Haidle has invited us down a rabbit hole that really leads nowhere. In between the tea parties and naughty games of doctor, Lucy carries on so many complex conversations about concepts (suicide, infidelity) blatantly beyond a 4-year-old's intellectual capacity that her nightmare world retains no grip on our imaginations or our emotions. It is too palpably shaped by the playwright, not by his character. (The snarky, portentous epigraphs for each scene do not help: "III. Concerning countless more hardships which Lucy endured with regard to her imaginary friends, if you can even call them that," runs one.)

The director, Michael Greif, and the actors bring a frenzied sense of fun to the play's lighter moments. It's hard to resist the sugar-shock food fight that Larry and Lucy embark on during a respite from their more sinister games, with Larry's somewhat more anodyne imaginary companions, a potty-mouthed cactus and sunflower, joining in. As Mr. Marmalade, Mr. Hall is flesh-crawlingly watchable as he twitches suddenly between roles as teddy bear in a business suit and abusive beast. In her Off Broadway debut, Ms. Gummer (a daughter of Meryl Streep) pouts and chirps childishly and effectively, even if she cannot mask the contradictions of her character.

But the gruesome excesses of Mr. Haidle's plot strike too many unearned sour notes. In exaggerating Lucy's self-inflicted emotional torture to spark spasms of nervous laughter, Mr. Haidle sacrifices the chance to explore his dark subject matter honestly. And you don't have to be a prig to wish that a playwright dealing with the idea of children's suffering would demonstrate an awareness that the subject is sadly not as far-fetched as the loopy tone would suggest.

Mr. Haidle does strive to end the play on a note of tentative hope. After Lucy has finally exorcised her demon, she is seen frolicking outdoors with Larry in a merry game of dodge ball, free at last from the terrors of her diseased imagination. But hold on, Mr. Haidle - dodge ball as a healing balm for toddler angst? In my experience, that infernal game was more likely to be the cause of trauma, not the cure for it. Heck, I've still got the emotional scars to prove it.

"Mr. Marmalade" continues at the Laura Pels Theater, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theater, 111 West 46th Street, Manhattan, through Jan. 29, 2006; (212) 719-1300.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment