ON THE TOPIC OF YOUNG MR. HAIDLE AND HIS FIRST BIG PLAY:

MR. MARMALADE

MR. MARMALADE

Copyright

by

Shawn LaCount

4/19/07

“My imagination runs wild. You have no idea.”

– 4 year-old Lucy, Mr. Marmalade

The New York Times called Noah Haidle’s Mr. Marmalade “a scary but ultimately hollow cartoon.”[1] A Curtain Up review of the play called it “a cheap, unappetizing mess.”[2] It is safe to say that his first production out of graduate school and his New York premiere with the Roundabout Theatre Company was a relative flop. It is noteworthy, then, that this flop thrust Noah Haidle’s name into the theatrical limelight and landed him main stage productions at some of the nation’s most prestigious theatres, including Connecticut’s Long Wharf Theatre, Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, Washington DC’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre, and Boston’s Huntington Theatre. Apparently, where critics have dismissed him, artistic directors have embraced him. Like it or not, Noah Haidle’s irreverent and controversial voice that fascinates artistic leadership and horrifies the media is defining the next generation of the American theatre.

Noah Haidle (pronounced High-dle) was born in 1980 and raised in Grand Rapids Michigan.[3] Planning on studying physics, he attended Princeton University before realizing that he “just wasn’t that good at math.”[4] As an English major he had the good fortune to take a playwriting course with Christopher Durang. After graduating in 2001, he went to Julliard for his graduate studies in playwriting. Under the tutelage of Durang and Marsha Norman, Haidle wrote more plays than any student in the history of Julliard’s program.[5] He wrote Mr. Marmalade in his first year. In his second, the play was produced by South Coast Repertory in Costa Mesa, California, and after that successful debut in 2004, Mr. Marmalade opened at New York’s Roundabout Theater Company in 2005, marking a rapid rise to the bright lights of off-Broadway for young Haidle.

In many of his plays, “Haidle places unconventional characters in often awkward situations to explore themes of desire, grief and humor in modern life.”[6] Even though Haidle claims to “have nothing new to say about the world,”[7] Jerry Tallmer has hailed him as one of “the most original voices” in American theatre.[8] His writing is highly theatrical and teeters on the absurd. Haidle is committed to this sense of theatricality: “One thing I don’t want to see in theater,” he said, “is any attempt at mimesis of reality. You’ve got TV and film, and they do it so much better; why try to top it in a medium where imagination can be freer?”[9] On the surface, Mr. Marmalade is certainly a far cry from reality, but what is disturbing is how realistically these fantastical characters experience their lives.

by

Shawn LaCount

4/19/07

“My imagination runs wild. You have no idea.”

– 4 year-old Lucy, Mr. Marmalade

The New York Times called Noah Haidle’s Mr. Marmalade “a scary but ultimately hollow cartoon.”[1] A Curtain Up review of the play called it “a cheap, unappetizing mess.”[2] It is safe to say that his first production out of graduate school and his New York premiere with the Roundabout Theatre Company was a relative flop. It is noteworthy, then, that this flop thrust Noah Haidle’s name into the theatrical limelight and landed him main stage productions at some of the nation’s most prestigious theatres, including Connecticut’s Long Wharf Theatre, Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, Washington DC’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre, and Boston’s Huntington Theatre. Apparently, where critics have dismissed him, artistic directors have embraced him. Like it or not, Noah Haidle’s irreverent and controversial voice that fascinates artistic leadership and horrifies the media is defining the next generation of the American theatre.

Noah Haidle (pronounced High-dle) was born in 1980 and raised in Grand Rapids Michigan.[3] Planning on studying physics, he attended Princeton University before realizing that he “just wasn’t that good at math.”[4] As an English major he had the good fortune to take a playwriting course with Christopher Durang. After graduating in 2001, he went to Julliard for his graduate studies in playwriting. Under the tutelage of Durang and Marsha Norman, Haidle wrote more plays than any student in the history of Julliard’s program.[5] He wrote Mr. Marmalade in his first year. In his second, the play was produced by South Coast Repertory in Costa Mesa, California, and after that successful debut in 2004, Mr. Marmalade opened at New York’s Roundabout Theater Company in 2005, marking a rapid rise to the bright lights of off-Broadway for young Haidle.

In many of his plays, “Haidle places unconventional characters in often awkward situations to explore themes of desire, grief and humor in modern life.”[6] Even though Haidle claims to “have nothing new to say about the world,”[7] Jerry Tallmer has hailed him as one of “the most original voices” in American theatre.[8] His writing is highly theatrical and teeters on the absurd. Haidle is committed to this sense of theatricality: “One thing I don’t want to see in theater,” he said, “is any attempt at mimesis of reality. You’ve got TV and film, and they do it so much better; why try to top it in a medium where imagination can be freer?”[9] On the surface, Mr. Marmalade is certainly a far cry from reality, but what is disturbing is how realistically these fantastical characters experience their lives.

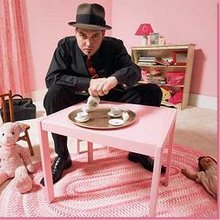

Mr. Marmalade is a play about Lucy, a four-year-old girl with a very active imagination. Her imaginary friend, Mr. Marmalade, unfortunately doesn’t have much time for her. Not to mention he beats up his personal assistant, has a cocaine addiction and a penchant for pornography. Larry, her only real friend, is the “youngest suicide attempt in the history of New Jersey.”[10] Lucy’s babysitter, who is fascinated with her own breasts, would rather “hook up” with her boyfriend than play tea party with Lucy. Like the title character, Lucy’s mom, Sookie, also appears to be preoccupied and unwilling to spend time with her own daughter.

As these characters might suggest, Mr. Marmalade is a savage black comedy that explores the darkest corners of a little girl’s imagination. It is a play that creates a strange “alternative universe” where children have a troubling sophistication and imaginary friends are anything but idealized and dependable. [11]

In Haidle’s universe, Mr. Marmalade is a twisted look at a disturbed 4 year-old in a horrifying and almost pornographic relationship with a grown man. There is little comedy about a drug addict hitting a child who refuses to have sex with him, but somehow Haidle gets us to laugh hard and often. With such outlandish absurdity, there must be a point to the madness. Mr. Marmalade could be viewed as a play that explores the minds of twenty-first century children who are overexposed and under-nurtured in every way. Lucy is an extreme case, to say the least, but there she is, fending for herself on every level. She has no father. Her mother works all day and at night brings home men that she dates. Lucy’s babysitter, Emily, who is paid to play with her, leaves Lucy alone, smoking and having sexual relations with her boyfriend instead. Quite literally, everyone in Lucy’s life has deserted her. And we must remember she is only 4, albeit with the worldliness of a twenty-something. Seemingly, the only thing Lucy can depend on is herself and the stories and characters in her head. These characters can only come from her experience and her perception of how the world works. It is noteworthy that her imaginary friends are both men. The only real men in her life are a stranger that her mom has a one-night-stand with, George, the babysitter’s over-sexed boyfriend, and 5-year-old Larry, who has bandages on both wrists. It is no surprise then, that her best friend in the world, Mr. Marmalade, follows suit and deserts her too. Abandonment issues abound.

The world premiere on the West coast was received far better than the play’s New York run. Young critics in California who appeared to be tired of the old ways of the theatre found hope in Noah Haidle’s emerging voice. The OC Weekly raved that “Mr. Marmalade at South Coast Repertory displays the vigor and staggering power that a straight play can deliver when done well. Playwright Noah Haidle is a 25-year-old who has crafted an apparently simple but convincingly unnerving play about a little girl whose imaginary friends and imaginarily bucolic home life are coping mechanisms designed to help her deal with brutal reality. It’s both a stirring elegy and a haunting examination of loneliness and desperate measures. Mr. Marmalade is a play worth seeing.”[12] By contrast, reviewers in New York uniformly disregarded the play as juvenile and shallow: The Times said the play “never truly capitalizes on its provocative conceit;”[13] New York Magazine called Marmalade “Another premise in search of a play” and, after cutting up the cast, in a patronizing attempt to look at the bright side of this fiasco, concluded “Fortunately they, like their playwright, are young and will recover.”[14]

Haidle claims to be not at all interested in theme; the concept for Mr. Marmalade, for example, started when he met his girlfriend-- “she had always wanted to be in a play wearing a tutu.” In divulging where his plays come from, Haidle quotes the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, “I was there and this is how life appeared to me at that moment.”[15] He claims to offer no direct comment on society. No intentional questioning of the American family. No analysis of early childhood development. He started with an image of a girl in a tutu and a man in a suit and asked himself, “Who was the man in the suit and what was he doing there with the girl in the tutu? And there you are--off to the races.”[16]

The playwright has gone so far as to say that, as an audience member, “you get from it what you bring to it” and that he distrusts writers who “want to coax an audience into some sort of feeling or thought provoking idea.”[17] Although Haidle is adamant that his plays are not at all biographical, he does admit to having known suicidal feelings related to loneliness. He also acknowledges that all of the characters come from different parts of himself. In a recent interview he confessed, “My heart is with Lucy. My dick is with Mr. Marmalade. My self loathing is with Bradley. And my pain is with Larry.”[18]

In addition to negative press, theatres (even on the west coast) had mixed response from their audience members as well. One letter to an editor read, "We're canceling our subscription to South Coast Repertory. It's become a red-light porno-district theatre."[19] Not entirely different, when Christopher Durang’s first professional production of The Idiots Karamazov premiered, Mel Gussow said “The Idiots Karamazov is, more or less, a musical comedy based on “The Brothers Karamazov,” which is enough to make Dostoyevsky turn over in his grave.”[20]

And the Yale Daily News wrote, "The Idiots Karamazov has no taste. It also has no reverence, no respect for the sacred, and no veneer of gentility.”[21] Although Durang’s premiere ultimately received more favorable reviews than Haidle’s Mr. Marmalade, the critique of the playwrights is similar. Both challenge convention and appear to have a penchant for risqué, irreverent humor. Interestingly enough, a young Meryl Streep starred in the world premiere of The Idiots Karamazov and her daughter, Mamie Gummer, starred in the Roundabout production of Mr. Marmalade.

Even with audience members threatening to cancel subscriptions, Artistic Directors around the country are readily attracted to the writing of young Noah Haidle. Tina Landau said of him, “Here’s a guy who writes a universe that’s really round -- funny, off-kilter, deep and poignant. He writes with an open heart.”[22] Robert Falls, the Artistic Director of the Goodman Theatre brought Haidle’s second major play, Vigils, to Chicago, saying, “I was impressed by Noah Haidle’s imaginative, provocative Mr. Marmalade off Broadway last year, and am pleased to give Chicago audiences the first glimpse of what’s next from this fresh voice in American theatre.”[23] Even before the first production of Mr. Marmalade premiered, Obie award-winning director Michael Greif (original production of Rent and Dogeaters) sought out Haidle and his scripts and asked to direct the off Broadway premiere of Marmalade. “I was excited by how theatrical his scripts were and how firmly they lived in a theatre setting. His plays are always founded in reality and peopled by characters who have true and real emotional arcs, but then Noah always manages to put them in some heightened context. This is especially important as we find ways to define theatre and its place in a world dominated by film and television.” [24]

Perhaps the largest compliments paid to Haidle are those large regional theatres like Boston’s Huntington that are currently commissioning new work by the playwright.

Artistic Directors, today, face a larger challenge than their predecessors. There is an apparent invested interest to hand the theatre from one generation to the next, but these theatres are not only responsible for marketing to a younger audience. Programming choices are forced to be inventive and groundbreaking as well. The new hot playwright needs to not only write the best play, but also must write a play that wins over movie goers, video game players, and internet surfers. As Artistic Directors flail to find the next big thing, the traditional audiences are slowly disappearing. Theatres across the country have been caught by surprise. Young people are not interested in subscription packages. Where theatres have been able to count on audiences buying into entire seasons in the past, new audiences don’t want to be tied down or committed.

Larger amounts of tickets are bought just prior to the show than ever before in the history of the theatre.[25] The question that Artistic Directors are asking themselves is what does this new generation of theatre-goers want to see? How can the theatre compete? Many have looked to playwrights like Noah Haidle, Adam Rapp and Gina Gionfriddo to begin to answer this question. In what seems to be the country’s dominating attitude of late, Mr. Marmalade has a sarcastic tone that suggests we are up a creek without a paddle and there simply is not much hope—at least until the next round of elections.

In the end, does Mr. Marmalade have anything to say? Does the play, as the New York Times’ Charles Isherwood believes, invite “us down a rabbit hole that leads nowhere?”[26] Where it may be easy to dismiss an early play by a young playwright, there may be more to this all American, Midwestern, Ivy League, prodigious young playwright’s story. Haidle may have tapped into something, though not entirely polished or intentional, that speaks volumes for where the American theatre is heading. Artistic directors are willing to take the risk of producing Haidle’s edgy work in order to lure younger audiences to their theatres.

Theatres around the country are clamoring to fill their seats with the generation Haidle represents. The playwright himself sits on the edge of the Millennial generation, and his point of view and call to action align with theatre-goers between the ages of 20 and 30. Most regional theatres are designing specific marketing campaigns targeting this demographic. Boston’s Huntington Theatre, for example, has tried selling packages of tickets and post show theatre events that resemble night clubs to lure in a more youthful audience.

The theatre has more competition in the digital age than ever before in history. In an era where the present generation of children does not know what it was like before the internet and cell phones took over, attracting people to the theatre is a daunting task. Haidle and playwrights of his generation are more attuned to this dilemma than some of his predecessors, and naturally write plays that incorporate elements of contemporary mass appeal while struggling to maintain a high level of artistry. Haidle concedes that “Part of the enjoyment of watching Mr. Marmalade is watching a twenty-something actor play a four-year-old and walk around in a tutu. Your imagination has to work harder as an audience member than it would watching film or TV. I take the play on two levels: One, it’s this alternative universe where children at age four attempt suicide, and, more significantly, have imaginary friends who are not very nice. At the same time, these child characters learn this imagined world from the real world that surrounds them. The conceit that this four-year-old has an imaginary friend who ends up acting like an abusive husband is very funny, I think.”[27]

The play appears to address America’s relationship with its children on many levels. Director Michael Greif comments, “On one hand we complain about kids playing graphic, violent video games and yet we’ll put a 12-year-old on trial as an adult for murder. At 18 they can die serving their country but they’re not old enough to have a beer. I think that part of the heartbreak of the play is the way Noah shows us how adults treat children, and the utter expendability and disregard they have for children’s innocence.”[28] This issue is at the forefront of the minds of these younger theatre-goers. Today, children have immediate access to anything they could want and that deeply affects their view of the world. According to Haidle, in Lucy’s case “things of course turn out badly.”[29]

Haidle is not alone in his questioning of modern American child rearing practices. The single working parent is more and more a common phenomenon. “Among kids of full-time working parents, 30 percent spend time in child-care centers and another 17 percent are cared for by nannies or sitters, a service industry with an average 1997 wage of $6.89 per hour. Many skeptics wonder what effect this will have on today’s kids.”[30] Many children have been known to create imaginary friends for themselves, most notably in their younger years. Reports of parents link their children’s losing interest in imaginary friends to the beginning of school where there is a greater opportunity to socialize with other children. In one sample, twenty-two percent of 700 4-year-olds were identified as having imaginary friends, where only three percent were identified in 7-year-olds.[31] The imaginary friend is prevalent in modern literature. From the Velveteen Rabbit to Puff the Magic Dragon, authors are confronting the age where young people disavow their relationships with their created figments and choose to live in the real world, where, say, kids play games like dodge-ball.

Haidle does a brilliant job at putting on display not only the range of influences that children are exposed to but also the high expectations that are put upon them to cope in this new world. Larry and Lucy represent different and extreme directions children can take. Even with its inherent comedy, there is an eerie truth and sadness when 5-year-old Larry admits to Lucy, “I mean, I don’t know if I’ve ever been happy before right now. You know how earlier I was saying I don’t get lonely? I was lying. I’m lonely all the time. Like always. Like for my whole life. That’s why I tried to kill myself.”[32] Lucy has her own journey, of course. Over the course of a day (which seems like a lifetime) she finds herself playing at tea party, cheating on and being abused by her husband, and finally playing a game of dodge-ball. As the hero of Mr. Marmalade, she has fought against the unreasonably difficult odds that have been stacked against her to simply win back her childhood.

And that is what it all comes down to. Haidle is a playwright writing for a generation submerged in extreme progress. His theatre offers a place where unsuspecting heroes can fight the dark demons of today’s world in order to win back a sense of stability, innocence and hope. Haidle may be a pornographer posing as a playwright or a young flash in the pan experiencing his 15 minutes of fame. Perhaps not. Like Lucy, Haidle is now on the fast track of growing up. He is being produced in the American theatre’s most prestigious institutions and will undergo the scrutiny of critics and subscribers alike. His development is a crucial part of what the theatre looks like today and what it will look like ten years from now. It is not our parents’ theatre. “It is disturbing, and it's about issues that need to be seen and confronted. Great art is open. There is a complexity to it. That's what makes it great art.”[33]

When asked about his own development, Haidle comments that he “wrote Mr. Marmalade in diapers” and wonders “how it could be taught anywhere.” He thoughtfully posits, “At its best I think writing is some sort of transcendent act of faith, of being present at the moment of its conception, and hoping that somebody else will find what you have written to be of some worth.”[34]

[1]Charles Isherwood. “A 4-Year-Old Who Needs A Divorce.” New York Times November 21, 2005

[2] Elyse Sommer. “Review: Mr. Marmalade” Curtain Up, 2005

[3] Linda Sullivan Baity. “Mr. Marmalade, part II- The playwright” South Coast Repertory Playgoers Guide April 16, 2004

[4] Tanya Palmer. “The Rise and Rise of Noah Haidle” On Stage: The Goodman Theatre, September 2006, p.13

[5] Sullivan Baity

[6] Anonymous. “Noah Haidle’s Vigils Set to Open” www.TheatreInChicago.com 2006

[7] Palmer, p.13

[8] Jerry Tallmer. “Take a Girl in a Tutu, a Man in a Suit, and Just Add Writer” The Villager, Volume 75, Number 23, Oct. 26, 2005

[9] Palmer, p.13

[10] Noah Haidle. Mr. Marmalade Dramatists Play Service Inc. 2006, Character List

[11] Christopher Durang. “Interview with the playwright” American Theatre Magazine February 2005, p.37

[12] Joel Beers. “Piss and Vinegar” OC Weekly May 6, 2004

[13] Isherwood

[14] Jeremy McCarter, “Seascape/Mr. Marmalade” New York Magazine, December 5, 2005

[15] Palmer, p.13

[16] Tallmer

[17] Noah Haidle interview by Shawn LaCount, March 4, 2007

[18] Haidle

[19] Durang, p.37

[20] Mel Gussow. “Play: Idiot’s Karamazov; Zany Musical” The New York Times November 11, 1974

[21] Laurel Graeber. “The Idiots Karamazov” The Yale Daily News November 14, 1974

[22] Palmer, p.13

[23] Anonymous. “Noah Haidle’s Vigils Set to Open” www.TheatreInChicago.com 2006

[24] John Istel. “Magical Marmalade” Roundabout Theatre Company: Front and Center Fall 2005

[25] TAMA, Public Survey, Theatre Alliance and Marketing Association (TAMA), 2006

[26] Isherwood

[27] Durang, quoting Haidle, p.37

[28] Istel

[29] Haidle, March 4, 2007

[30] Neil Howe & William Strauss. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation Vintage Books 2000

[31] Marjorie Taylor. Imaginary Companions and the Children Who Create Them, Oxford University Press, 1999, p.133

[32] Noah Haidle. Mr. Marmalade, Dramatists Play Service Inc. 2006, p.23

[33] Istel

[34] Haidle, March 4, 2007

Bibliography

Anonymous. “Noah Haidle’s Vigils Set to Open” Theatre In Chicago.com 2006

Beers, Joel. “Piss and Vinegar” OC Weekly May 6, 2004

Durang, Christopher. “Interview with the playwright” American Theatre Magazine February 2005

Graeber, Laurel. “The Idiots Karamazov” The Yale Daily News November 14, 1974

Gussow, Mel. “Play: Idiot’s Karamazov; Zany Musical” The New York Times November 11, 1974

Haidle, Noah. Mr. Marmalade, Dramatists Play Service Inc. 2006

Howe, Neil & Strauss, William. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation Vintage Books 2000

Isherwood, Charles. “A 4-Year-Old Who Needs A Divorce.” New York Times November 21, 2005

Istel, John. “Magical Marmalade” Roundabout Theatre Company: Front and Center Fall 2005

LaCount, Shawn. From an interview with Noah Haidle March 4, 2007

McCarter, Jeremy “Seascape/Mr. Marmalade” New York Magazine, December 5, 2005

Palmer, Tanya. “The Rise and Rise of Noah Haidle” On Stage: The Goodman Theatre, September 2006

Sommer, Elyse. “Review: Mr. Marmalade” Curtain Up, 2005

Sullivan Baity, Linda. “Mr. Marmalade, part II- The playwright” South Coast Repertory Playgoers Guide April 16, 2004

Tallmer, Jerry. “Take a Girl in a Tutu, a Man in a Suit, and Just Add Writer” The Villager, Volume 75, Number 23, Oct. 26, 2005

TAMA, Public Survey, Theatre Alliance and Marketing Association (TAMA), 2006

Taylor, Marjorie. Imaginary Companions and the Children Who Create Them Oxford University Press, 1999

[2] Elyse Sommer. “Review: Mr. Marmalade” Curtain Up, 2005

[3] Linda Sullivan Baity. “Mr. Marmalade, part II- The playwright” South Coast Repertory Playgoers Guide April 16, 2004

[4] Tanya Palmer. “The Rise and Rise of Noah Haidle” On Stage: The Goodman Theatre, September 2006, p.13

[5] Sullivan Baity

[6] Anonymous. “Noah Haidle’s Vigils Set to Open” www.TheatreInChicago.com 2006

[7] Palmer, p.13

[8] Jerry Tallmer. “Take a Girl in a Tutu, a Man in a Suit, and Just Add Writer” The Villager, Volume 75, Number 23, Oct. 26, 2005

[9] Palmer, p.13

[10] Noah Haidle. Mr. Marmalade Dramatists Play Service Inc. 2006, Character List

[11] Christopher Durang. “Interview with the playwright” American Theatre Magazine February 2005, p.37

[12] Joel Beers. “Piss and Vinegar” OC Weekly May 6, 2004

[13] Isherwood

[14] Jeremy McCarter, “Seascape/Mr. Marmalade” New York Magazine, December 5, 2005

[15] Palmer, p.13

[16] Tallmer

[17] Noah Haidle interview by Shawn LaCount, March 4, 2007

[18] Haidle

[19] Durang, p.37

[20] Mel Gussow. “Play: Idiot’s Karamazov; Zany Musical” The New York Times November 11, 1974

[21] Laurel Graeber. “The Idiots Karamazov” The Yale Daily News November 14, 1974

[22] Palmer, p.13

[23] Anonymous. “Noah Haidle’s Vigils Set to Open” www.TheatreInChicago.com 2006

[24] John Istel. “Magical Marmalade” Roundabout Theatre Company: Front and Center Fall 2005

[25] TAMA, Public Survey, Theatre Alliance and Marketing Association (TAMA), 2006

[26] Isherwood

[27] Durang, quoting Haidle, p.37

[28] Istel

[29] Haidle, March 4, 2007

[30] Neil Howe & William Strauss. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation Vintage Books 2000

[31] Marjorie Taylor. Imaginary Companions and the Children Who Create Them, Oxford University Press, 1999, p.133

[32] Noah Haidle. Mr. Marmalade, Dramatists Play Service Inc. 2006, p.23

[33] Istel

[34] Haidle, March 4, 2007

Bibliography

Anonymous. “Noah Haidle’s Vigils Set to Open” Theatre In Chicago.com 2006

Beers, Joel. “Piss and Vinegar” OC Weekly May 6, 2004

Durang, Christopher. “Interview with the playwright” American Theatre Magazine February 2005

Graeber, Laurel. “The Idiots Karamazov” The Yale Daily News November 14, 1974

Gussow, Mel. “Play: Idiot’s Karamazov; Zany Musical” The New York Times November 11, 1974

Haidle, Noah. Mr. Marmalade, Dramatists Play Service Inc. 2006

Howe, Neil & Strauss, William. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation Vintage Books 2000

Isherwood, Charles. “A 4-Year-Old Who Needs A Divorce.” New York Times November 21, 2005

Istel, John. “Magical Marmalade” Roundabout Theatre Company: Front and Center Fall 2005

LaCount, Shawn. From an interview with Noah Haidle March 4, 2007

McCarter, Jeremy “Seascape/Mr. Marmalade” New York Magazine, December 5, 2005

Palmer, Tanya. “The Rise and Rise of Noah Haidle” On Stage: The Goodman Theatre, September 2006

Sommer, Elyse. “Review: Mr. Marmalade” Curtain Up, 2005

Sullivan Baity, Linda. “Mr. Marmalade, part II- The playwright” South Coast Repertory Playgoers Guide April 16, 2004

Tallmer, Jerry. “Take a Girl in a Tutu, a Man in a Suit, and Just Add Writer” The Villager, Volume 75, Number 23, Oct. 26, 2005

TAMA, Public Survey, Theatre Alliance and Marketing Association (TAMA), 2006

Taylor, Marjorie. Imaginary Companions and the Children Who Create Them Oxford University Press, 1999

No comments:

Post a Comment